Famille Gassier is one of the premier vineyards the southern Rhône Valley in the south…

UK Government Farming Policy: Agri-Cultural Extinction?

Apologies for the sensationalist headline, but it’s clear the future of farming in this country is at a crossroads. In fact, you’d be forgiven for thinking that the current (unwritten) UK government policy is to dismantle ‘UK farming’ as we know it.

I’m not one for conspiracy theories but it appears that independent family farms (and the long-standing rural economic and social dynamic that surrounds and depends on them) will soon be replaced by large scale agribusiness – and the welfare and environment consequences that come with it. Whether it’s planned policy or just the collateral damage of incompetence, the outcomes will be the same.

Like many of you, I was dismayed at the recent news in the farming and mainstream media that the future of farm support in England has once again been brought into doubt after leaks revealed that Defra might be ‘overhauling’ (read ‘trashing’) the Environmental Land Management Schemes (ELMS), .

ELMS was devised as a way to provide financial incentives or support for farmers and landowners to make changes to their land that resulted in positive environmental benefits. The idea is that ELMS would effectively replace the old Basic Payment Scheme (BPS), which acted as a safety net for farmers by supplementing their main business income. BPS payments made to farmers are reducing each year until 2027, when they will end completely.

The end of the Basic Payment Scheme (BPS) was justified with the promise of a “Green Brexit” and the redirection of subsidy to achieve positive environmental outcomes on the farm. What we now have is the continued phase out of BPS and no idea of what the support for producing environmentally sound, healthy food will look like – or even if it will exist at all.

A report published in January by the Public Accounts Committee (which examines the value for money of Government projects, programmes and service delivery) predicted that the average farmers will see a 50% reduction in income from direct government payments by the 2024-5 financial year, which may be a death sentence for some businesses. Likewise, the National Farmers Union predicted that livestock farmers will have lost between 60% and 80% of their income by 2024 as a result of these reductions.

A wholesale restructure of UK farming in favour of intensive production at scale is the inevitable outcome. This is only going to be accelerated and exacerbated by the effects of pointlessly profligate (and largely Brexit face-saving) deals such as those with New Zealand and Australia allowing cheap imports of beef and sheep meat, as former Defra minister George Eustice has shockingly pointed out. It’s just a shame he didn’t have the mettle to stand up for his constituents before he signed the deal. (Note that British beef is still banned in Australia.)

Farming requires sensible long- and medium-term planning. Changes made at the stroke of a pen to national farm policy cannot be so easily or quickly implemented on the ground; unless, of course, you just quit the industry (and even that takes some planning and execution). Sadly, I fear the quit option will become increasingly attractive unless we have some clear direction from government that allows farmers to plan.

Cynically, I do wonder if existentially the options are already in front of us, and that this current government sees UK farmers as no longer an important constituency (if we ever were) and would just prefer we quietly go out and let global market forces alone determine what our rural culture and environment looks like.

UK farming has come a long way in the 25 years I’ve been involved in farm certification and the conversation around farmed animal welfare, water, soil and biodiversity has never been more focused. This has been driven and encouraged by directed subsidy coupled with (some) prudent legislation. Perhaps ironically, over recent years Defra civil servants (led by the impressive Janet Hughes, Programme Director of Future Farming and Countryside Programme) have worked more closely than ever with farming and environmental organisations and, crucially, individual farmers to develop a subsidy system through ELMS that was generally regarded as realistic and workable on the ground and effective in its outcomes. A rare achievement.

But while no agricultural subsidy system is perfect, we now face the real risk of throwing away the advances that have been made and exposing UK farming to the rapacious winds of international trade, forcing many farmers down the road to intensification – or out of business. The animal welfare, environmental and social outcomes that such intensive farming systems have produced in certain parts of the world are not something any of us would like to see replicated here.

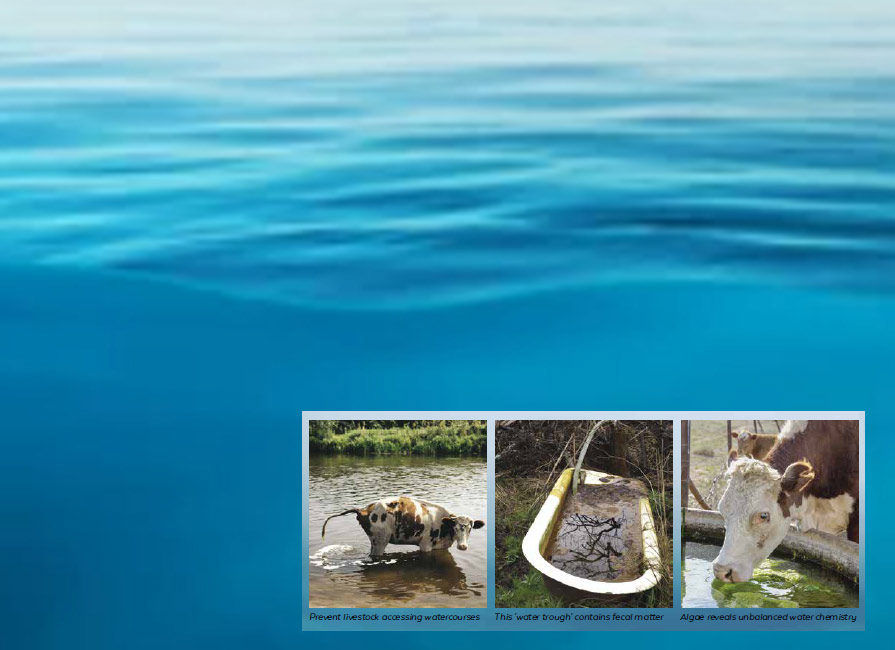

Photo credit: Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS)